https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-these-renaissance-artists-took-art-out-of-the-church-and-into-the-home

George Philip LeBourdais

The Most Iconic Artists of the Northern Renaissance, From Dürer to Bosch

Spanning two centuries—from around 1380 to 1580—the was the period in which the artistic practices and humanist ideals of Renaissance Italy migrated north across the Alps, and flourished in Germany, the Netherlands, and France. The movement is epitomized by the Dutch humanist scholar Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam, whose critical satires of the Catholic Church opened the door for the Protestant Reformation.

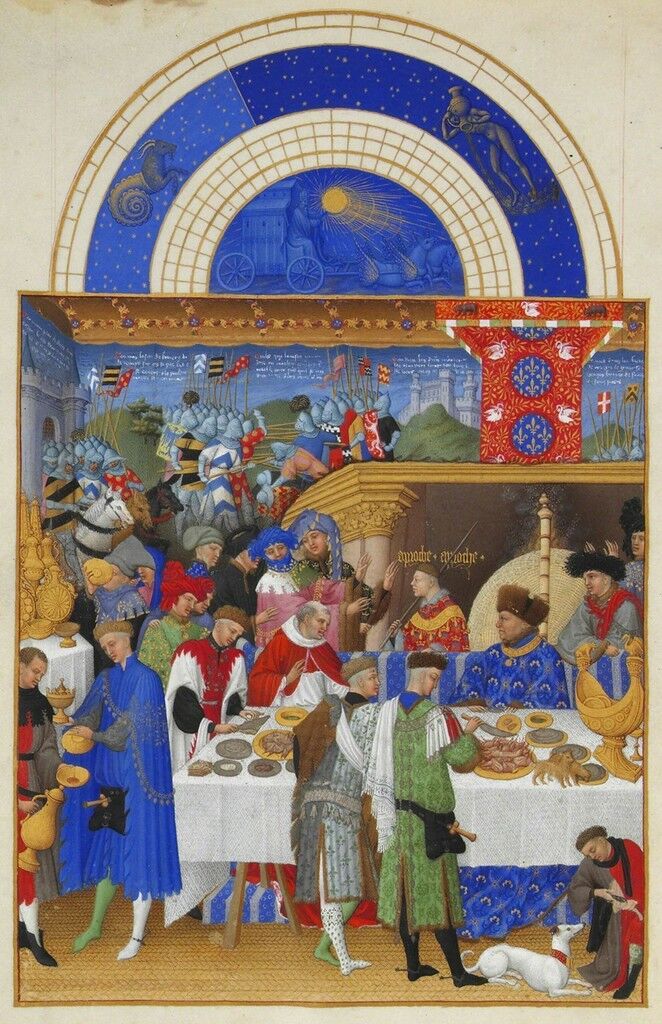

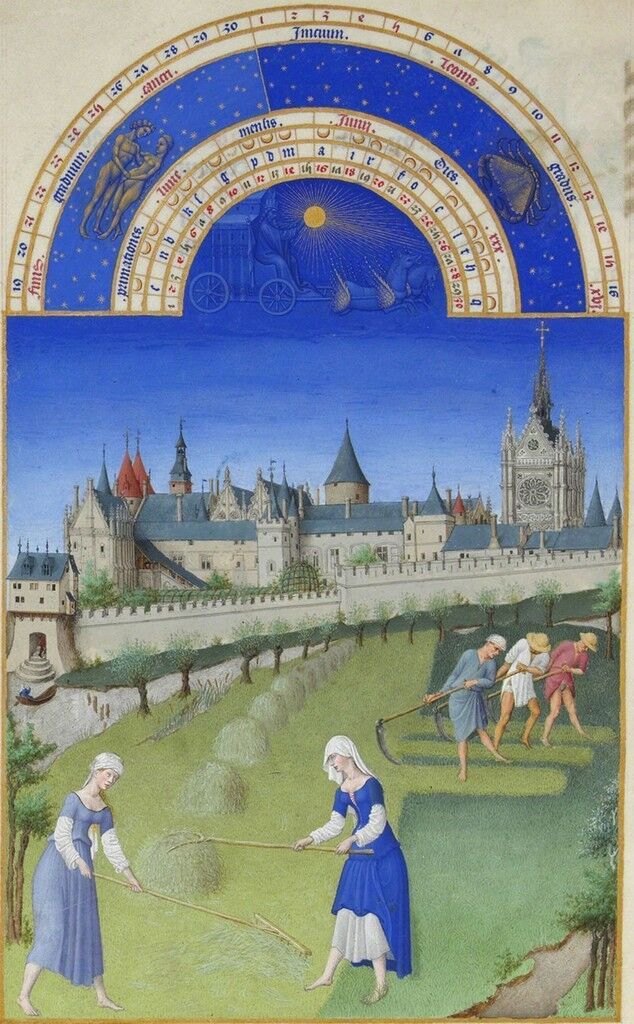

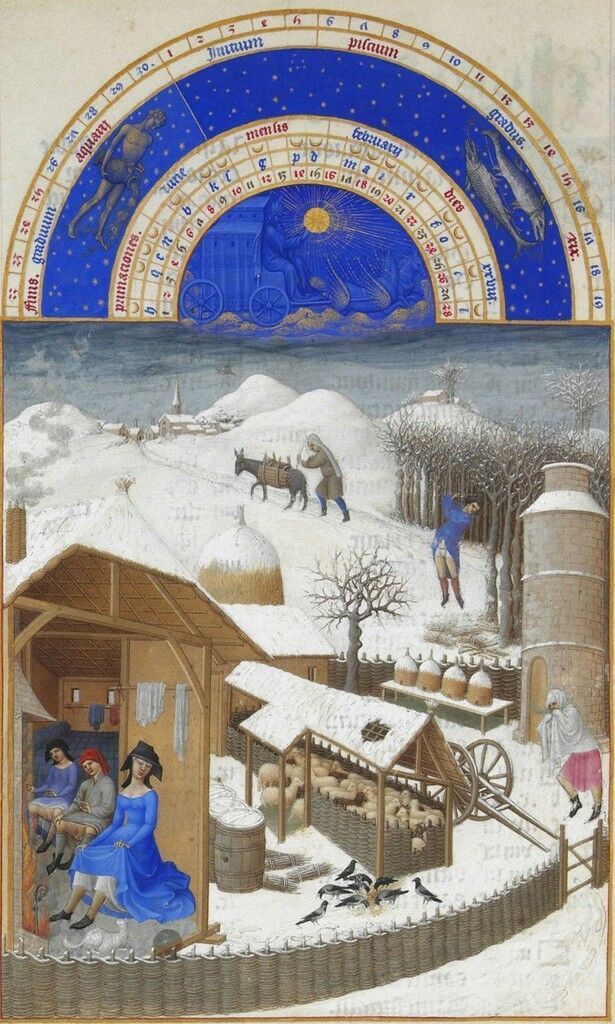

The Northern Renaissance is marked by several overarching features: the blossoming of artistic centers in the Burgundian Netherlands, Southern Germany, and Paris; the proliferation of art for use in both the church and the home; and technical advancements in the realms of oil paint, printmaking, and sculpture that led to new modes of representation. The arc of these developments emerges in the work of the , three Dutch manuscript illuminators active in France at the beginning of the 15th century. Their collective masterpiece, the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (1411-16), a book of hours created for Jean, Duke of Berry, is considered the pinnacle of the International Gothic style, and its naturalism and attention to detail inspired numerous subsequent artists.

Naturalism was certainly the concern of , who is now identified as the Master of Flémalle. Based in the Flemish town of Tournai, the artist maintained a highly productive atelier that employed other important artists, like , and created work for local civic and religious institutions. The greatest artwork attributed to this group is the Merode Altarpiece (ca. 1427–32), a triptych believed to depict the Annunciation—the moment when the angel Gabriel informs Mary that she will be the mother of Jesus. The work is now housed at The Cloisters, the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s medieval European collection. In the central panel, the meeting between Mary and the angel Gabriel occurs in an intimate, domestic setting. Both figures have a weighty, worldly presence that grounds them in the space, their physicality underscored by heavy folds of brightly colored drapery. Joseph is pictured in his workshop on the right, while the donors are depicted on the left.

As for the period’s heightened attention to detail, one need look no further than (ca.1380–1441). The Dutch artist was the official painter to Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, and had a meticulous style that has been described as “microscopic-telescopic vision.” The intricate rendering of fabric, jewels, gold, and even the hair of God the Father’s beard in the central panel of the multi-paneled Ghent Altarpiece (ca. 1432) are all celebrated examples of this precision. This masterwork, van Eyck’s magnum opus, was begun by Jan’s brother Hubert van Eyck. The two worked together on the altarpiece, which Jan finished after Hubert’s death. Jan achieved such fine details through his early adoption of and developments in oil paint. Suspending pigments in oil allowed them to be applied in layers, wet-on-wet, which created translucent glazes as well as an unprecedented intensity of color.

Jan van Eyck

Sint Baafskathedraal

Jan Van Eyck was also innovative in his use of subject matter, as demonstrated in his Arnolfini Wedding Portrait (ca. 1434). At a time when private portraits were still rare, van Eyck depicts an Italian merchant and his wife standing in a bedchamber. The source of much interest and research, the painting is thought to be a visual document attesting to the marriage it represents, and is thus full of symbolic objects with distinct iconographies: the dog connotes faithfulness, the removed shoes imply the space is hallowed ground, and the mirror on the back wall signifies the immaculate nature of the young bride. The artist’s own reflection in that mirror, like his signature on the wall above it, indicates that van Eyck served as a kind of witness to the ceremony.

As double portraits go, the one produced in the summer of 1533 has achieved even greater notoriety. The Ambassadors affirms the meeting of Jean de Dinteville, then French Ambassador to England, and Georges de Selve, the Bishop of Lavaur. Like van Eyck, Holbein reproduces the attending objects in the finest detail to transform the image into a document of sorts. Europe is visible on the globe, while recent mathematical treatises and musical scores from the period are clearly discernible.

So precise are these replications that viewers might initially overlook the strange, slanting form in the center foreground. When viewed obliquely, from the side or from above, the object becomes legible as a gray skull, revealing the complex significance of the painting as a memento mori (a reminder of death). As in perspectival experiments during the Italian Renaissance, Holbein uses scientific approaches to painting to challenge subjective positions, compelling viewers to question their place in the world.

Though Holbein was the best-known painter in England during the Reformation, was the artist most responsible for transmitting principles to the North and spurring the development of a distinctly Northern style. Considered by many scholars to be the greatest German artist, Dürer was a polymath on the order of southern counterparts like or , producing paintings of the highest order. His self-portraits, including the last he completed in 1500, at age 29, reveal new Renaissance conceptions of the artist: aristocratic, business-minded, and with God-given talents.

But Dürer also revolutionized printmaking, elevating it to the level of fine art. While many may be familiar with his whimsical The Rhinoceros (1515), the woodcuts from his “Apocalypse” series (1497–98) portray the late-Gothic narrative and emotional intensity with the virtuosic handling of line and shading for which Dürer became internationally revered. Continued advancements in linear perspective and anatomical study come to bear in Melancholia I (1514), one of his later master engravings, showing off some of the earlier intersections of art and science.

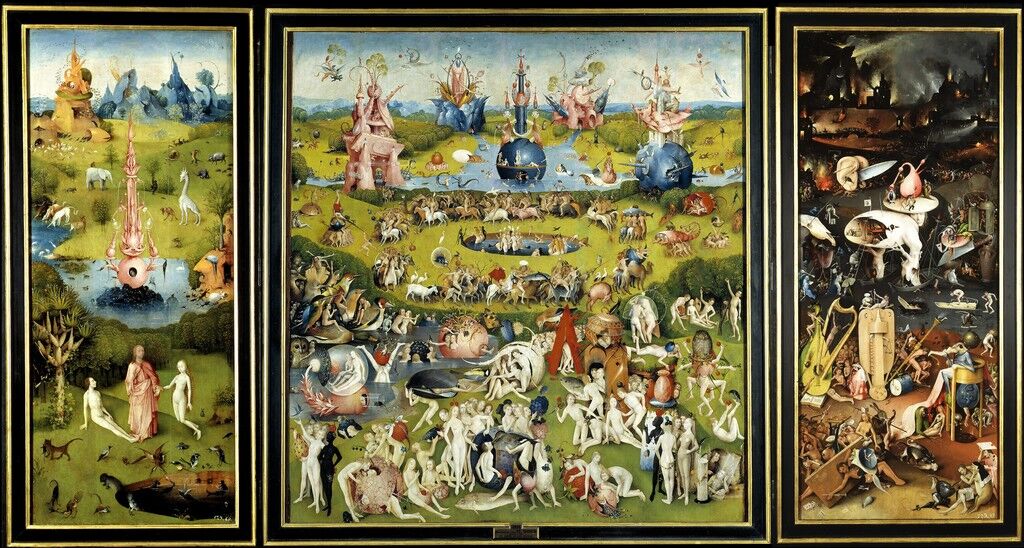

Detail views of Hieronyumus Bosch, Garden of Earthly Delights, ca. 1505-15. Collection of Museo del Prado, Madrid; image via Wikimedia Commons.

While Dürer transformed Biblical scenes with Renaissance style, infused them with fantasy. His most famous work, The Garden of Earthly Delights (1505–15), combines alternately comic and demonic vignettes into grotesque landscapes. A triptych, it depicts a progression of human sin across three panels, with the Garden of Eden at left, the imperfect human world at center, and the horrors of Hell at right. Each group plays out its own scene of gluttony, debauchery, and other fleshly transgressions.

One scene (right panel, left side, bottom third) imagines sonic retribution for those who, in life, used music as a means of seduction and temptation. Instruments here —harp, lute, hurdy-gurdy—have been transformed into huge instruments of torture. Two sinners are crucified on a hybrid lute-lyre, while, below, a choir of sinners and slithering things scream a score inscribed on buttocks, a song to the organ of lust it surrounds. Across many other alarming and alluring episodes, Bosch weaves realism, allegory, and fantasy together.

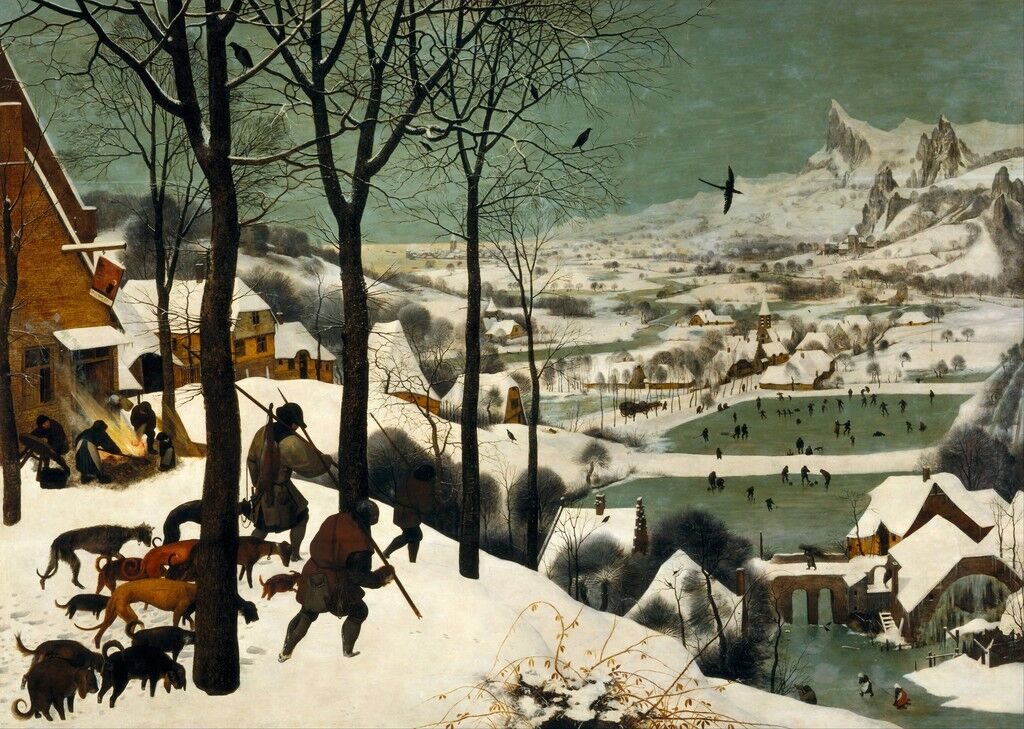

Although several allegorical landscapes by may have led to his reputation as a “second Bosch,” the artist’s works are worlds apart, rooted deeply in everyday human behavior. In Dutch Proverbs (1559) and Children’s Games (1560), for instance, Bruegel playfully translates common sayings and axioms into visual vignettes. But he is perhaps better known for quieter, more contemplative works like Hunters in the Snow (1565), part of a calendar-like series of landscape scenes created for a wealthy patron. With seasonally keyed colors, diagonal lines leading to distance points, and aerial perspective in the far-off snowy mountains, Bruegel unites techniques from both Flemish and Italian traditions.

Indeed, these works paved the way for further developments in Dutch art as the turn of the 17th century approached, leading to what is known as that republic’s Golden Age. George Philip LeBourdais

The Deadly Truth behind Pieter Bruegel the Elder’sIdyllic Winter Landscapes

Pieter Bruegel the Elder

The Hunters in the Snow, 1565

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

To many, ’s winter landscapes—the first significant scenes of their kind in European art—impart an atmosphere of festivity. Indeed, the Flemish artist’s quaint snow scenes can often be seen on the front of Christmas cards. The figures in the paintings skate on frozen rivers, play early versions of ice hockey with sticks and rocks, or attempt to catch birds. Above all, they seem to marvel at the stark beauty before them. But this picturesque sense of revelry has largely been conjured centuries later, by viewers who have evolved ways of protecting themselves from winter’s force.

In Hunters in the Snow (1565), one of the most famous images in Western culture, three men and their dogs—soggy, exhausted, and hunched against the cold—trudge home from a hunting expedition. They reach the edge of a hill, catching a glimpse of the winter wonderland stretched before them in the valley below. Bruegel similarly introduces the viewer to the expansive landscape through the hunters’ point of view; the eye enters the painting on the left, following their footprints across the snowy bank.

But for the artist and the ordinary folk populating his winter works, these images would have been bittersweet, if not foreboding: At the time these paintings were made, they were living through a period of intense climate change now known as the “Little Ice Age.”

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Adoration of the Magi in the Snow, 1563. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

The term was first used in 1939 to describe a period of 4,000 years, but has since been narrowed by scientists to denote the intense cooling that occurred between roughly 1300 and 1850, some of the most fruitful centuries in art history. Within this span, many credit the 1560s as the first decade of extreme weather, and 1564–65 is cited as the coldest winter of the century. Hunters in the Snow and Bruegel’s other famous snow scenes—including Winter Landscape with Skaters and Bird Trap (1565) and The Census at Bethlehem (1566)—were born from these events.

During this time period, rivers froze solid enough that locals were able to open rent-free marketplaces on them. Trees produced wood so hardy and unique that from it, created the best musical instruments the world had ever seen. But food shortages were almost yearly, inciting riots and illness throughout Europe. Suicide rates rose. Many people thought the destruction of their crops or deaths of their children were punishments from God, or they blamed witchcraft for their misfortunes—claims that resulted in the deaths of thousands of women.

In 1560, a red sky over Northern Europe was interpreted in religious pamphlets as a divine omen. As if in answer, there was pestilence in Austria and summer storms throughout Europe for the rest of the century. In 1563, 63 women from the southern German town of Wiesensteig alone were burned at the stake. Over 30 years later, the King James I of England’s treatise on witchcraft, Demonology, mentioned the use of magic to make the weather worse. It was an obsession of the age, also reflected in works like William Shakespeare’s Macbeth and the Faust legend, first printed in 1587.

Closer to home for Bruegel, the theologian Johannes Molanus recorded the winter of 1564–65 as being “harsh beyond measure,” a time of terrible flooding in the region of Brabant, where it is speculated that Bruegel was born. He wrote about paupers getting frostbite and losing noses, hands, and genitals to the cold. Birds fell dead from the sky. (Bruegel would go on, in The Massacre of the Innocents, 1565–67, to put the brutality of these abnormal winters to the service of a biblical brutality, in what could be seen as an example of pathetic fallacy wildly ahead of his time.)

This is the world in which Bruegel lived and painted.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Census at Bethlehem, 1566. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Before these extreme winters began, Bruegel had traveled throughout Italy. “While he visited the Alps, he had swallowed all the mountains and the cliffs, and, upon coming home, he had spit them forth upon his canvas and panels,” reads Karel van Mander’s fanciful account of Bruegel’s biography, written after the artist’s death, in 1604. Although somewhat unreliable, Van Mander’s writing on Bruegel remains the closest thing to a portrait of the artist, and it’s clear that these mountains did have a deep effect on the artist: In the top right corner of Hunters in the Snow, he transposed alpine peaks on the depicted rural village typical of the Low Countries.

Bruegel single-handedly made winter landscapes subject matter fit for serious painting. Previously, they might feature in tapestries and prints, occupy the corners of larger works, or be seen in the margins of illuminated manuscripts. It seemed that the harsh winter had gotten into Bruegel’s bones; the cold would quickly become absolutely essential to his way of seeing. For his first attempt at translating snow in paint, The Adoration of the Magi in the Snow (1563), Bruegel would almost entirely obscure Mary, Joseph, and the infant Jesus with a blizzard. Largely due to the popularity of Bruegel’s snow scenes—of which copies by his son, , and other artists were widely circulated—a whole new genre was embraced by 17th-century Dutch painters, as well as wealthy patrons.

The merchant Nicolaes Jonghelinck commissioned Hunters in the Snow as part of a sequence of six panels about the seasons—each painting illustrating two months of the year—to hang in the dining room of his suburban home near Antwerp (only four other paintings of the group survive today). Hunters in the Snow depicts the harsh midwinter months of December and January. The others show ordinary people involved in all kinds of agricultural work during the planting and harvest seasons. But Hunters creates a hiatus in the natural narrative progression of the series, one that reflects the sort of formal holiday Flemish communities took during the winter months.

The human figures here are doubly halted: frozen by the weather and in time by paint, just as the pace of life slowed during the agricultural off-season. Today when the weather is bad, public schools and offices shut, public transportation is disrupted, and people are snowed into their houses. In Bruegel’s landscape, diligent hunters have trekked out into the woods, only to return with a single small fox. Down below, a stooped figure carries bare, brittle firewood over a bridge; this person is a sort of mockery of the women in Haymaking (1565), who carry baskets of fruit on their heads in the warm summer months of June and July.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Winter Landscape with a Bird-trap, ca. 1601. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

In Hunters, Bruegel’s subjects eke out what joy they can from the punishing environment, just as the artist found beauty in a scene his contemporaries certainly wouldn’t have viewed as resplendent. Bruegel has not depicted a bright winter day—his scene is overcast, almost gloomy. The sky hovers between steel blue and malachite, a color reflected in the sheets of ice covering the river.

Here, Bruegel is a of snow, his renderings at once impressionistic and true to life. Like Turner, the artist’s ability to capture the versatility of snow with various textures further adds poignancy to the composition. Look at the hunters’ footprints; one can feel the weight of the man closest to us as he sinks into the snow. See how well he captures the qualities of all the other elements battling against the cold. For instance, the smoke and flames from the fire before the inn on the left—as in the Census at Bethlehem, painted a year later—seem almost smudged, giving an impression of pure motion. Looking at this icy yet undoubtedly beautiful work, there is a sense that Bruegel hovered between an impulse to shear winter of its terribleness while also trying to show its harsh beauty. Perhaps in the end, he couldn’t make up his mind, but the ambiguous result is startlingly powerful.

Hunters in the Snow is far from a Christmas card scene, but it does highlight some silver linings that chroniclers observed during this dangerous peak of the Little Ice Age. Locals sensed opportunity in the cold, building markets and attractions on frozen rivers and ponds; they played games that we still enjoy today. People pulled together in this adversity, and Hunters in the Snow captures their resourcefulness, endurance, will to survive—and ability to find spare joy in a cold climate. Bruegel’s paintings celebrate man’s relationship with nature, no matter how punishing.

It’s a fitting time to reflect on Bruegel’s winter paintings, which are all the more important today as we again experience such extreme weather due to human effects on the environment. Global warming will involve a constant refrain of Little Ice Ages. Bruegel reminds us that there’s beauty in the cold.Jonathan McAloon

===============================================================