10 Things You Didn’t Know About Giorgio Vasari

From scandalous gossip to sumptuous paintings, Giorgio Vasari helped shape the Italian Renaissance. This article unpacks everything you need to know about the father of art history.

Born in the Republic of Florence in 1511, Giorgio Vasari was in prime position to watch the Renaissance unfurl over the course of the sixteenth century. He was not happy, however, to be a passive spectator. He involved himself in all manner of artistic developments and built a wide circle of influential friends around him. Discover more about the father of art history over the following 10 facts.

10. As Well As Being A Writer, He Was Also A Painter Himself

Like an increasing number of elite young men, Giorgio Vasari was brought up in the world of art, having trained under the painter Guglielmo da Marsiglia in his hometown of Arezzo and then with Andrea del Sarto in Florence.

Having witnessed the work of some great High Renaissance artists first hand, Vasari took a different approach in his own paintings. He was part of the Mannerist movement that reacted against the harmony and clarity prized by the likes of Leonardo da Vinci and Raphael, replacing these features with a more exaggerated, obscure and complex style. Like his artistic forebears, however, Vasari still incorporated a rich use of color, tricks of perspective that give his paintings depth, and profound subject matter, often religious.

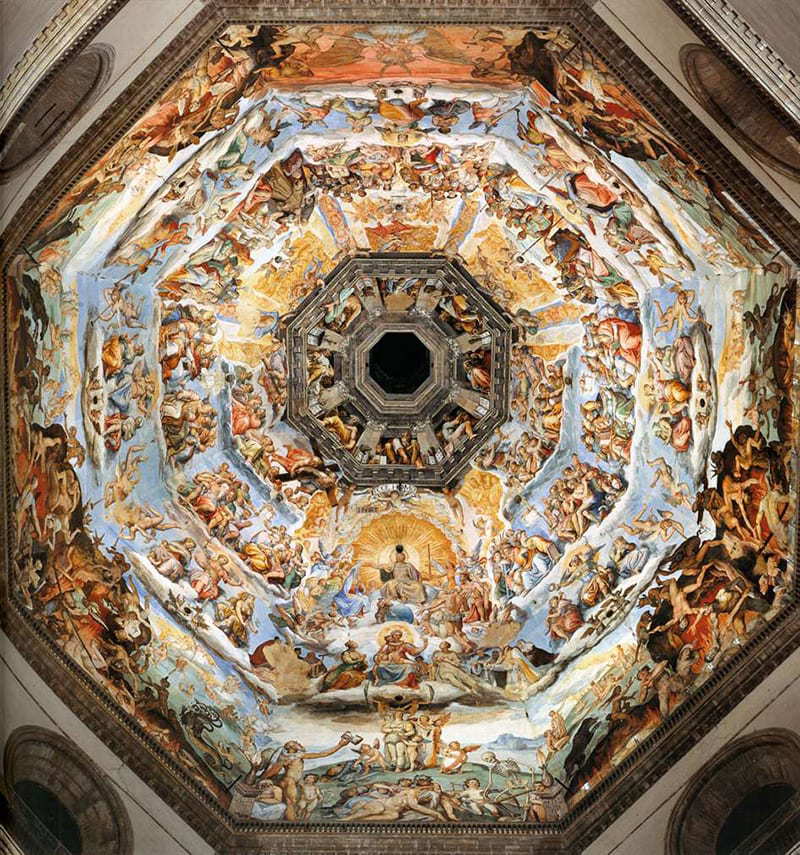

Vasari’s Mannerist paintings won him great renown during his lifetime, and earnt him some important commissions. These included the chancery of the Palazzo della Cancellaria in Rome, and the interior fresco of the cupola on Florence Cathedral.

9. He Was Not Only A Homme De Lettres, But Also Put His Artistic And Technical Skills Into Practice As An Architect

Like many of the sixteenth century elite, Vasari was something of a polymath. He constructed the loggia of Florence’s Palazzo degli Uffizi, where crowds now queue for hours for admission into the world-renowned Uffizi Gallery. The loggia, which embraces the Arno at its south end, is practically unique as a cross between an architectural structure and a street.

He performed the vast majority of his architectural work on churches across Tuscany, remodeling two of Florence’s churches in the Mannerist style, and constructing an unusual octagonal dome for a Basilica in Pistoia. He adorned the Santa Croce with a painting commissioned by the Pope, and provided the epic fresco for the inside of Florence Cathedral’s magnificent cupola.

8. He Was Directly Employed By The Most Important Renaissance Family

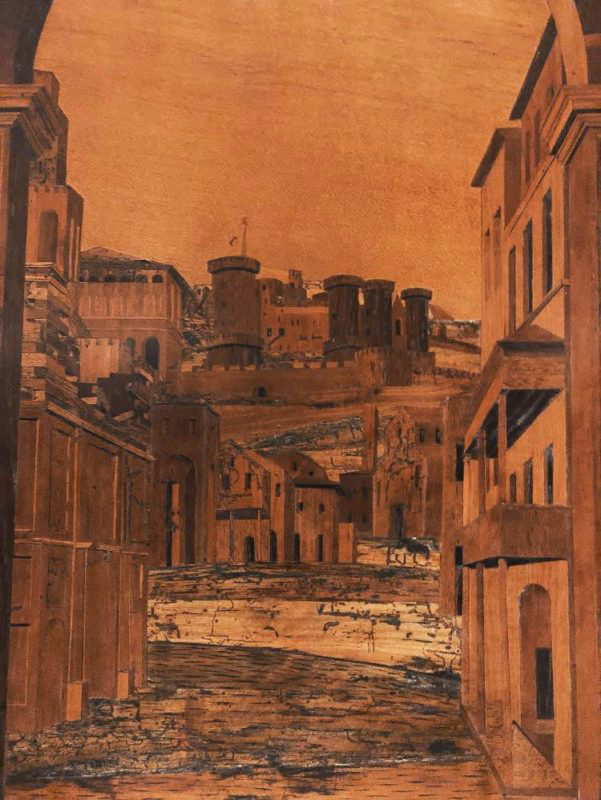

Vasari’s talents attracted the attention of some influential patrons, namely the Medici family. On the commission of Cosimo I, he painted the vault frescoes of the eponymous Vasari Sacristy in Naples, as well as the wall and ceiling paintings in his patron’s own rooms of the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence.

Working for Italy’s most powerful family provided Vasari with the connections, funds and experience he needed to expand his influence among Europe’s elite circles.

7. Vasari Was One Of Italy’s Most Well-Connected Artists

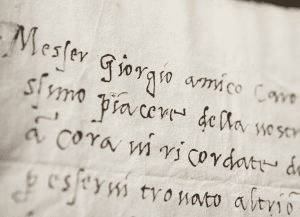

In the artists’ studios of Florence, Vasari had mingled with a number of other aspiring artists as a young man. Most notable among these was Michelangelo, who would prove a lifelong inspiration and friend. Their correspondences still exist, with each man heaping praise on the other, and Michelangelo even composing a poem to celebrate Vasari’s talent.

As Vasari became a more prominent artist, his network of connections grew, and he eventually counted Giorgione, Titian and many other Renaissance artists among his acquaintances.

6. As Well As Peers, He Acquired A Strong Following Of Younger Artists

Vasari may have been inspired by the likes of Michelangelo, but many great younger artists found their inspiration in him. These young men were mainly based in Arezzo, where Vasari had his first studio.

Among them were the famous fresco painter, Carducho, who later emigrated from Italy to Spain to work for Philip II. As was typical for the time, Vasari enlisted the help of these apprentices for some of his major projects, such as the cupola of Florence Cathedral, which was actually completed by his assistant Federico Zuccari.

5. These Acquaintances Equipped Him With Everything He Needed To Compose His Magnum Opus

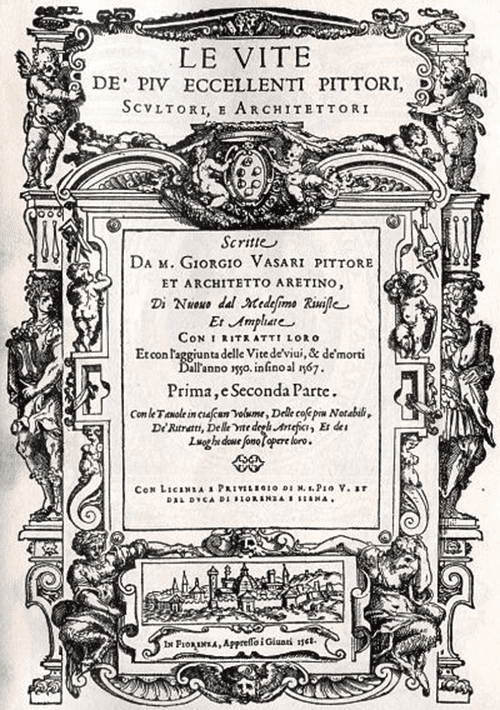

In 1550, Vasari published a collection of biographies, compiled under the title Le Vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori, ed architettori (The Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors and Architects). This encyclopedic work was dedicated to Cosimo I and consisted of hundreds of accounts documenting the lives of Europe’s most famous artists. It is infamous for the scandalous gossip and amusing anecdotes Vasari reveals. From the sexual misdemeanors of Giovanni Antonio Bazzi, nicknamed ‘Il Soddoma’, to the many irrational fears and vexations of Piero di Cosimo, the author refuses to spare even the most intimate details.

Although Vasari worked on The Lives rigorously, there are numberless errors, inaccuracies and biases. Unsurprisingly, he gives most of the credit for Renaissance developments to the Florentines, deliberately excluding the craftsman of Venice from his first edition. However, in the second, enlarged edition (1568) he does include Titian.

A particularly famous stories appears in Titian’s biography: Vasari had arranged a meeting between Titian and Michelangelo. After exchanging compliments to one another, the two Florentines left and swiftly began to complain about how poor the Venetian’s drawing actually were.

4. As Well As Providing An Amusing Source Of Scandalous Gossip, The Lives Of The Artists Marked An Important Moment In Art History

In compiling The Lives, Vasari became responsible for the first modern work of art history. In fact, he paved the way for all future art historians by showing that the theory and analysis of art could be just as valuable as its creation.

It is in the pages of The Lives that the word ‘Renaissance’, or ‘Rinascita’, is first printed, an important moment in the history of art. Vasari was also the first author to use the term ‘Gothic’ in relation to art, as well as introducing the concept of economic ‘competition’ into the field of painting.

3. His Talents Made Vasari Richer Than Many Of His Famous Friends

The Medici patronage and popularity of The Lives meant that Vasari amassed a vast fortune during his life. He occupied a wonderfully grand house in Arezzo that he had built and decorated himself, and married the daughter of one of the town’s richest families.

Vasari’s prestige also continued to grow as he became older: the Pope made him a Knight of the Golden Spur and he later founded an artistic academy in Florence alongside Michelangelo. His material wealth and social influence proved that Vasari had truly reached the pinnacle of Italy’s elite.

2. His Legacy Has Remained Just As Impressive

The Lives has rarely been out of print since it was first published, remaining an invaluable tool for art historians and amateur enthusiasts alike. So popular has it proved that rare or early editions of the work regularly sell for huge sums of money. In 2014, for instance, an example of the important 1568 edition sold at Sotheby’s for £20,000.

Vasari’s legacy has also permeated into popular culture, with his famous fresco of The Battle of Marciano appearing as a clue in Dan Brown’s famous book, Inferno. The characters investigate the mysterious ‘cerca trova’ (‘seek and find’) message painted on a distant banner, and also scrutinize the works hung in the Vasari Corridor in the Palazzo Vecchio.

Vasari Himself Was An Avid Art Collector

As well as being a ‘collector of lives’, Vasari also gathered a huge collection of art through his relationships with the Renaissance’s most prominent craftsmen.

As part of his role in the Medici’s employ, Vasari was responsible for curating and displaying the family’s vast archive of paintings and sculptors, essentially transforming the Medici court into a museum or gallery. His aim was to immortalize the memory of Italy’s greatest artists.

At the age of 17, Vasari received a gift of drawings from the grandson of Lorenzo Ghiberti, a gesture which inspired him with a life-long appreciation of drawings, which were often overlooked in favor of completed paintings. He eagerly collected sketches over the following decades, which led to their acceptance as valuable pieces of art. Naturally, Vasari also received countless paintings from his admirers and students, growing a collection that cemented his position as one of art history’s most important figures.

READ NEXT:

Leonardo da Vinci: Bio, Works, and Trivia